Mashipo 馬屎埔

It was a surprisingly cool mid-afternoon as our group finally reached what had once been the Mashipo wetlands, which used to cover the area from the river to well beyond the Fanling metro station. We lingered on the sidewalk looking over the densely grown bushes and jerry-rigged assemblages forming the boundary fencing of individual plots. On first inspection, it looked like a vital place: there was a hand-painted sign indicating an organic farmers market near a sheltered post-box unit, and an intermittent flow of pedestrians and cyclists of various ages maneuvered down the concrete paths that strayed into the lush interior, where well-kept houses of corrugated metal were guarded by zealous dogs. Finally our guide, a 60-something year old retired land surveyor (“Not for the developers!”) named Raymond, came out on one of these paths to meet us, and swiftly led us in along toward his land. It was late February but the plants we passed appeared to be in mid-growth (perhaps only notable if you consider the several months until the soil in Beijing takes on the appearance of anything but desiccated silt). Raymond halted briefly at a series of several quadrants where the ground was fastened with tiles and concrete. Here had once stood shacks housing families. Henderson, one of the largest real estate companies in Hong Kong, had been buying up such properties, piece by piece, and either flattening them or smashing them out like gaping lifeless examples in order to unsettle those who still remained. Raymond’s eyes sparkled as he explained his plan (in perfect English, for my sake): to occupy one yard with festival tents or other makeshift shelters, and refuse to leave until the real estate company took them to court to force removal; then—gesturing gingerly with his arms—he would move the entire occupation a few meters over to the yard “next-door,” repeating the process whenever they received a new notice, and then start all over, therefore dragging any possible removal into some indeterminate future. I asked him whether he had tried this tactic before, and he smiled and said, not yet, but I think it should work.

Moving along, we stopped near an area of turned earth that had been sprinkled with a white powder. Raymond indicated that this would be where they would grow yellow ginger to sell at cost to the pregnant mothers of Hong Kong; without a profit, he stressed, so that the people will understand what our purpose is. And this was just the beginning of the plans for the lengthy strip of land on which we were standing. Raymond’s father-in-law had occupied this government-owned land as tenant in 1960, which was then, ironically, licensed to him by the government in 1970, when it was zoned for agriculture. In the last few years, as was mentioned above, the land has been leased (land can only be leased from the government in Hong Kong, as in PRC) in portions to Henderson to develop apartment high rises. Even if the area we were standing on did not itself become a construction site, development of the sections that had already been bought would basically render the area unfit for cultivation because of the shadows the buildings would cast. The consultancy period for the development of the area had been due to be completed in 2012, but already resistance to the plan had resulted in a delay to the project of 4 years. In the meanwhile, Raymond and his family, as well as a group of young activists and others, are planning a number of projects to further resist and delay the development of the area, involving as many parties as possible.

As it stands, there are a number of others farming the land, not all of whom have necessarily signed on for the resistance to Henderson and the government. Some of these (apparently mainland Chinese) people come from the large complexes across the road and just want a spot to grow their own vegetables. But lacking knowledge of organic or traditional methods of growing or land management, they have no second thoughts about using pesticides or about lopping off the branches of a perfectly healthy lychee tree (that now had rubber boots inverted on the branch stubs). Such practices were all more self-evidently faulty to the people who had actually been living on the land next to the growing crops. And indeed, not many people actually live on the land anymore. This marks the endeavor of Raymond and his allies as somewhat different from other well-known examples of agriculture, activism and culture uniting in civil resistance against the loss of farm lands and traditional lives at the hands of government and developer collaboration. One of the most well-known of these struggles was the opposition to the Hong Kong–Shenzhen–Guangzhou express rail link, which caused the demolition of Choi Yuen Tsuen and displaced its villagers in a process spanning from 2009–2011. Though the loss of the village is long foregone by now, the resistance actions that included petitions, protests and artistic/activist cultural projects are still felt through a legacy of publications, documentaries, online discussions, and more importantly, through a lasting coalition of efforts that came together and carries over to other fields and new challenges. “There are hundreds of Choi Yuen Tsuens,” I was told, and some of the spirit of possibility carries over to Mashipo. The plan of Raymond and the others, however, is not only based on the injustice of displacement, but about proposing an alternative to the craze for destroying green and natural areas: “a showcase for traditional agriculture.”

Winding our way along a path past a giant mulberry tree and the small house where Raymond’s 90-year old father lives, and through a field of blossoming dill, chamomile and other flowering vegetables, we came to a grove of banana trees and a thin corridor of tall grass on the edge of a stream hidden by undergrowth. Raymond described his plan to construct a mud and straw house in a traditional Guangdong style, his tone sounding urgent since this is best done in the winter. This house had to be built now, but so did the many other initiatives that would go nowhere if brought as proposals to the government first; the key was to simply start doing things. Other ideas included a fish pond, which would also demonstrate cultivation of aquatic flowers, a community kitchen and a composting process, and in the fields, an emphasis on local herbs and vegetables; in short an eco-system that would make good use of this fertile soil. One of the city-based organizers involved in the Mashipo project, Kim Ching, showed me their layout for an edible garden. I asked whether they were reaching out by organizing an allotment system for people to come and grow, or by holding farmers markets or some sort of experimental farming school. (Raymond kind of groaned when I mentioned the sign advertising the organic farmers market I had seen back by the road, explaining that he and others had started it but that now, run by different people, mostly cheap organic produce flooding in from from Mainland China is sold there.) But I was quickly corrected: “Not only a farming school—but everything, public gatherings—in fact, almost everything is related to farming.”

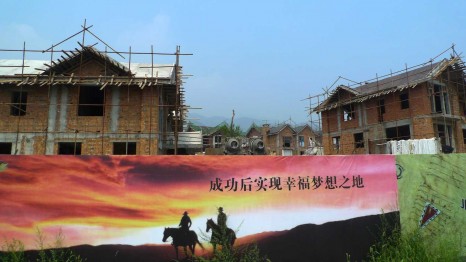

The impetus behind Mashipo, then, is the construction of public space, in light of (or in spite of) its decimation by the CEOs of both Hong Kong’s administration and its corporations. This form of awareness and discourse was refreshing in a place that is effectively under control of the mainland Government, which also makes it seem fragile. As we looped back toward the street, the heavy evening sky darkened and fused with the curtain of mountains that form the backdrop for the skinny high rises clustering the New Territories. We turned around toward the north and Raymond pointed out some towers looming in the distance spelling out words with LEDs on their ostentatious surfaces. That’s Shenzhen right over there, he said. You can see how convenient it will be to drive down and stop here overnight before getting on the metro to your meetings in the morning, he mused rather reasonably. This observation betrayed no ignorance of the forces they are up against. And with my limited knowledge, I considered how unlikely this situation would be back in Beijing or elsewhere on the mainland: a 4-year delay because of complaints? Was this the patronizing local government appeasing environmentalist nostalgia for the sake of an appearance of validity, or what? (Could it actually be a soft-spot for democracy?) Setting aside doubts about the potency of the deputy authorities and their games, such a delay would certainly be grasped by the citizens of Hong Kong for its possibility to cultivate much more than a few feral papayas. Much more.

(originally posted on the HomeShop blog, 14/03/2012)